Dr. Felisa Smith | Smith Lab

Dr. Felisa Smith | Smith Lab

Bio:

Felisa Smith is a Distinguished Professor in the department of Biology. A conservation paleoecologist, she integrates modern, historic and fossil mammal records to investigate pressing environmental issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Over her career she has worked on organisms from microbes to mammoth, but vastly prefers the latter. Most recently Smith has been using the terminal Pleistocene megafauna extinction as a proxy for understanding modern mammal biodiversity loss. In addition to her 3 books, she has written~120 papers/book chapters in a wide variety of scientific journals, and taught scientific blogging at UNM (http://unm-bioblog.blogspot.com). She has participated in many audio and video programs including National Public Radio, BBC World Service, BBC Earth, and BBC’s Horizon series, German public radio, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and the History Channel as well as numerous print interviews/essays. Felisa was elected a Fellow of the Paleontological Society in 2020, was awarded the Merriam Award from the American Society of Mammalogists in 2022, and is the 68th recipient of the UM Annual Research Lecturership in 2023. She is currently the President of the American Society of Mammalogists and Past President of the International Biogeography Society.

Abstract:

The conservation status of large-bodied mammals is dire. Their decline has serious consequences because they have unique ecological roles not replicated by smaller-bodied animals. Here, we use the fossil record of the megafauna extinction at the terminal Pleistocene to explore the consequences of past biodiversity loss. We characterize the isotopic and body-size niche of a mammal community in Texas before and after the event to assess the influence on the ecology and ecological interactions of surviving species (>1kg). Pre-extinction, a variety of C4-grazers, C3-browsers, and mixed-feeders existed, similar to modern African savannas, with likely specialization among the two sabertooth cats for juvenile grazers. Post-extinction, body size and isotopic niche space were lost, and the δ13C and δ15N values of some survivors shifted. We see mesocarnivore release within the Felidae: the jaguar, now an apex carnivore, moved into the specialized isotopic niche previously occupied by extinct cats. Puma, previously absent, became common and lynx shifted towards consuming more C4-based resources. Lagomorphs were the only herbivores to shift towards C4 resources. Body size changes from the Pleistocene to Holocene were species-specific, with some animals (deer, hare) becoming significantly larger, and others smaller (bison, rabbits) or exhibiting no change to climate shifts or biodiversity loss. Overall, the Holocene body size-isotopic niche was drastically reduced and considerable ecological complexity lost. We conclude biodiversity loss led to reorganization of survivors and many ‘missing pieces’ within our community; without intervention, the loss of Earth’s remaining ecosystems that support megafauna will likely suffer the same fate.

Dr. Smith at Texas Memorial Museum

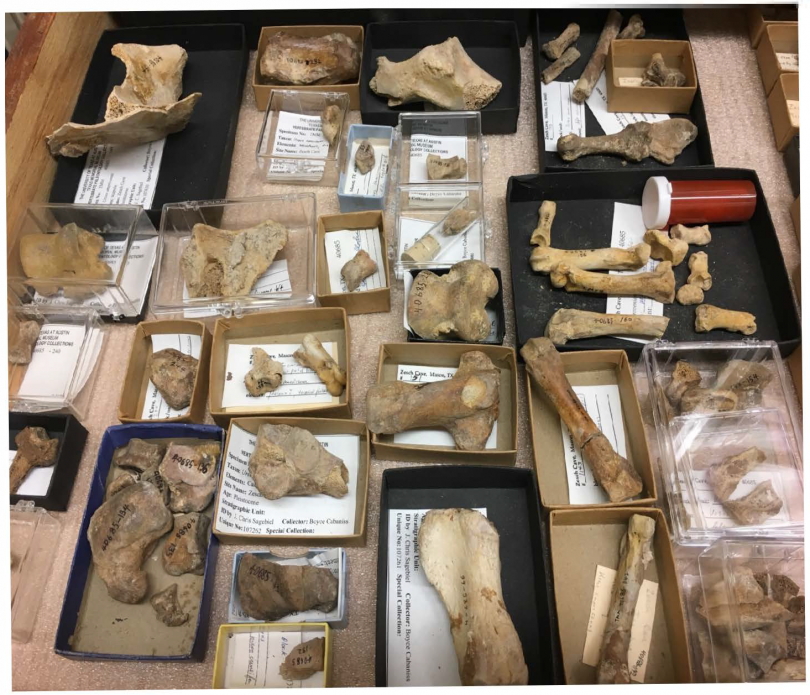

Fossils under study

Cave art showing human hunting